Ласкаво просимо в Україну

“To tell the truth, most people in the travel community said that we are crazy. And for many people, as you know, visiting Syria, Afghanistan, Libya is considered to be safer than going to Ukraine. And there is a reason for that because Ukraine is at full-scale war. And what we are doing is something really, really extraordinary. Guys, this is scary.”

This is how Ukrainian Orest Zub starts this episode. And he’s right. Visiting a country during a war can be an endeavour filled with uncertainty and risk. As travellers, understanding the potential dangers of conflict zones, such as Ukraine, is crucial. This isn’t just about potential risk to personal safety; it’s also about respecting the people and the situation within the country.

Understanding the ethics of such visits, the precautions to take, and the realities of safety within the country can shape our approach towards such extraordinary travels, enhance our cultural sensitivity, and redefine our perspective on conflict zones.

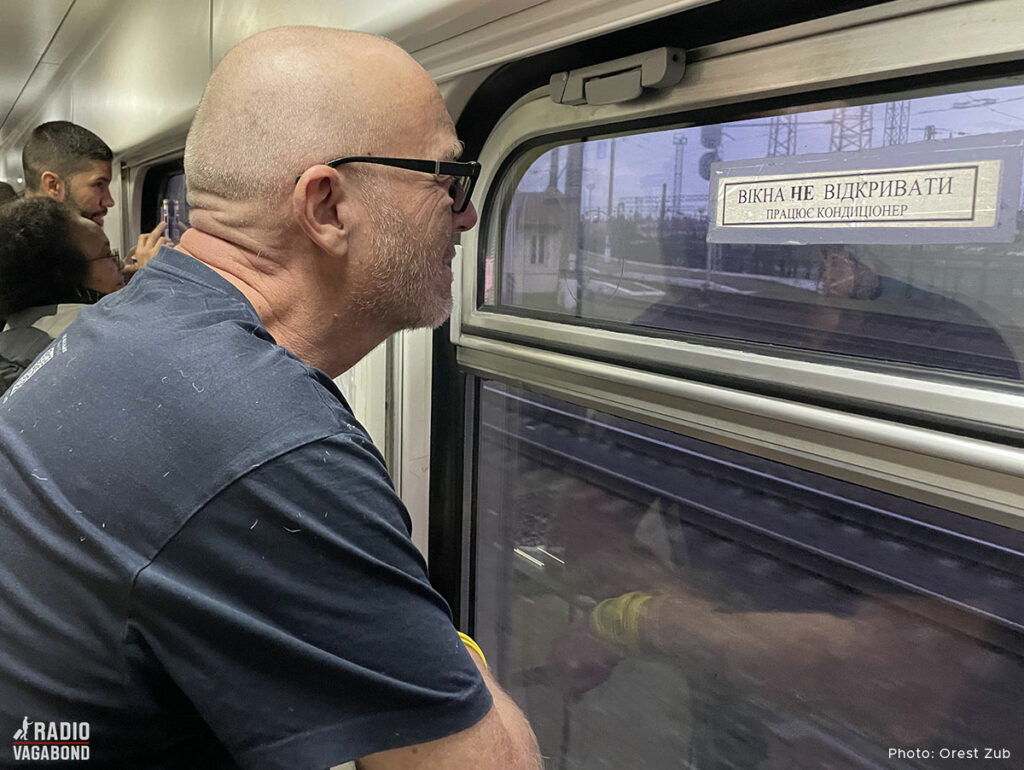

After spending ten days in Kraków, Poland, I got on the train three hours east to the Polish border city with a hard-to-pronounce name: Przemyśl [SHEH-mih-shuhl]. This is where we meet the group and cross the border by train the following day.

I know a few people, but the first two I met for the first time. An English policeman, Shaun Brannan and Tony Wang, a young Kiwi of Chinese descent who teaches competitive math.

When I ask them why they decided to join the trip, Shaun says:

“Well, myself, I was looking at spending a bit of extended time in Ukraine for a few years. Obviously, the war happened and it kind of put me on the back for a little bit. But when I saw this coming up on Orest’s YouTube channel, I just thought it was a good opportunity for me to visit Ukraine with a few more people with something that’s a little bit more guided. Give me the opportunity to have a look around.”

Shaun mentioned Orest Zub. And that’s a name you will hear many times in these episodes from Ukraine. I’ve already had him on The Radio Vagabond twice. First when we met in Croatia in June 2022 and then again a few months ago when we talked about this visit to Ukraine in a special episode.

Orest is a 35-year-old Ukrainian who travelled extensively before and even after his country was invaded. During the war, the government asked him to fight the media war and help bring awareness to the outside world about what is happening in Ukraine. He does that on his YouTube channel and by attending and speaking at events around the world so the world doesn’t forget there’s a war in Ukraine even when it becomes “yesterday’s news”, like when something horrible happens in the Gaza Strip or other places around the world, so the country keeps having the support of the rest of the world.

And he also does it by organizing this tour. He lives in Lviv in the safer western part of the country with his wife Marta Trotsiuk – also an accomplished traveller.

Here’s Tony on why he decided to join this tour:

“Well, personally, I don’t have as much of a history with Ukraine, but I saw this opportunity, and I might not get such an opportunity again in my life. I mean, I certainly don’t hope there’s another war within Europe within my life. So, I thought this would be a good opportunity to kind of see a war first-hand.”

“See a war first-hand,” Tony says. And you might be thinking, “Why?”… “Why in the world would anyone want to see a war first-hand?”

I know, that was what my family said when I told them I was going to Ukraine, a country at war.

Understanding the Risks of Visiting a Country at War

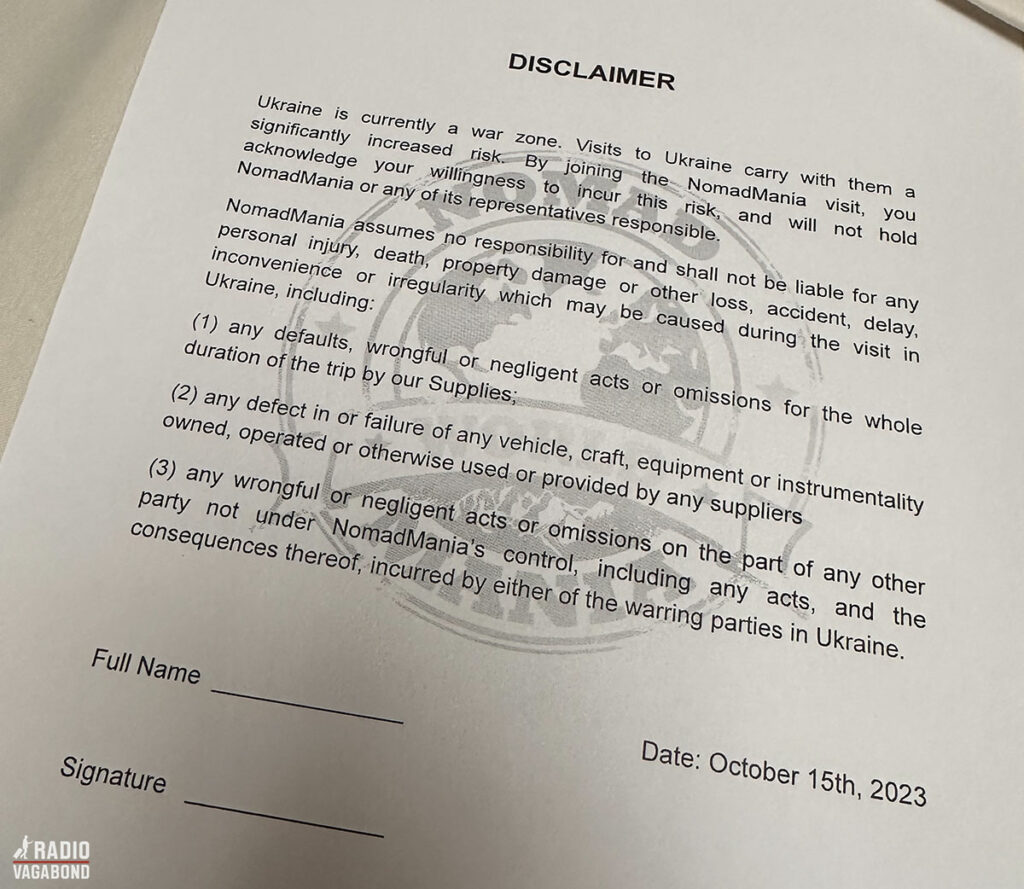

For me, it was because it allowed me to show my support to the Ukrainian people and tell their story – right here on The Radio Vagabond. But I’m not a war correspondent and don’t take crazy risks. So, I did a lot of research before saying yes, when Orest Zub and Harry Mitsidis, the founder of NomadMania, asked me. Part of the research was doing the podcast episode with Orest a few months ago, talking about safety.

During travel preparations, understanding the risks associated with visiting a country at war is critical for your safety. Gaining comprehensive knowledge of potential hazards and volatile situations enables travellers to properly prepare and adapt their plans accordingly.

Our experience was marked by caution and exhilaration in undertaking a journey of this nature. We were constantly aware of our surroundings, double-checking our safety measures and being selective of the paths and areas we chose. For instance, keeping our plans under wraps, disabling location settings on our devices, and strictly adhering to sealed roads in potentially landmine-infested areas became normal procedures for us.

We had first-hand experience of how quickly danger can approach when a rocket hit close to our hotel shortly before our visit. This heightened our vigilance and reinforced the real nature of the risks of travelling in a war-torn country.

Also, visiting a country during war can be an ethically complex decision. The realities of war include personal and societal suffering that may not be immediately apparent to a visiting outsider. Therefore, any decision to travel to a conflict zone should be informed by a thorough understanding of the local context and a demonstrated commitment to respect and support local communities. A personal visit can express solidarity and, when done responsibly, offer hope and encouragement to the people living through the conflict. Every trip we make leaves a footprint, and in such sensitive regions, we must ensure that ours embodies kindness, respect, and understanding.

Arriving to Lviv

After breakfast the following day, we meet at the Przemyśl train station, cross the border, and get on the train to Orest’s home city, Lviv in the western part of Ukraine.

The Lviv Railway Station is an impressive architectural landmark. The main building features a neoclassical architectural style with elements of Baroque and Renaissance influences. It has a grand, imposing facade with large columns, decorations, and a central clock tower.

The building is painted in a pale yellow or cream colour, giving it a distinct and elegant appearance.

Inside the station, we find a spacious and well-maintained waiting hall with high ceilings and large windows, allowing ample natural light to fill the space.

The interior is full of historical details, creating a sense of grandeur and history. There are shops, kiosks, and cafes with snacks, refreshments, and souvenirs.

The Lviv Railway Station, with its historic and elegant architecture, is a transportation hub and a significant cultural and architectural landmark in Lviv. It reflects the city’s rich history and offers a welcoming and convenient space for travellers arriving in or departing from Lviv.

During the beginning of the invasion, over 50,000 people were passing through the station as refugees from east to west every day. Many shelters and tents were outside the station for people waiting to get on the train to Poland.

As we arrive and admire the building, we see that this country is at war. The police and the military had closed the station – most likely after a bomb threat had been phoned in. And Orest had to talk to them to let us through.

We’re only staying in Lviv for a few hours before returning to the train to go east. This is partly to drop off the bigger bags at the hotel we’ll be back at in a few days, to get lunch, and a local SIM card for those who need that. But we start with a cup of coffee as Orest gives us a safety briefing.

Precautions when in Conflict Zones

When embarking on a journey to a conflict zone like Ukraine, it is essential to tread lightly and stay vigilant. One key takeaway from this experience is the importance of understanding the place’s current situation, being conscious of safety measures, ensuring discretion about your travel plans, and staying respectful of the situation. It involves understanding that areas prone to ongoing conflict can continually change, and security and safety measures must be continually updated and monitored.

Safety Briefing

In the safety briefing, Orest is telling it as it is:

“Ukraine is at a full-scale war and there is a frontline. But this frontline is basically stagnant for the recent month. So it’s not moving, and there is no way it can expand very quickly. And most of the destructions you will see comes from the artillery fire. Artillery can shoot no further than 30 km, which means that everything beyond the artillery range can be considered relatively safe.”

Artillery fire includes various large-calibre firearms such as cannons and mortars. The range of artillery fire can vary based on the type of artillery piece and the specific ammunition used.

Some typical examples of artillery ranges include short-range artillery, such as mortars, which typically have a range of up to a few kilometres, and medium-range artillery, like field guns and howitzers, can have ranges of several kilometres, often up to 30 kilometres (20 miles). We will never be closer than 30 kilometres from the front line, so we only have to worry about missiles and landmines.

Also, Orest tells us that we (as a group of foreigners) could technically be a target.

“Let’s say, somebody sees that a group of 20 foreigners as a legitimate military target, and they want to hit just us, which is very unlikely. We are not that important in the grand scheme of things. In order to hit something with an artillery missile, you need preparation, intelligence, coordination, and coordinates, which means that it’s very unlikely our bus will be hit with the missile, because it’s simply moving around.”

This is why we weren’t given any details on where exactly we would be going. All we knew before the trip was that we were going to Lviv, Kharkiv and Kyiv before going back to Lviv. Not how we would get there and where we would be staying.

Also, we were all asked to turn off the location settings on our phones when we left Lviv so we couldn’t be tracked.

A Missile Attack close to Our Hotel

We will be in Kharkiv on the 16th of October, and something happened ten days earlier.

Yes, Orest received a phone call two days after booking and paying for our hotel in Kharkiv for the group. It was the manager of the hotel, Reikartz Kharkiv, who told him that a Russian rocket had hit just 50 m from the hotel entrance, damaging the front side of a building, and many other buildings in the area had their windows blown out.

“But don’t worry”, he said. “We have changed some of your rooms. And otherwise, everything’s fine.”

Fine? Orest thought to himself. He told me that he felt like the universe was telling him he was playing with fire. I can only imagine the internal dialogues Orest had back then.

But as for missile attacks, it’s about being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Orest calls it “Russian roulette”, and it literally is.

Land Mines

There’s another risk: Landmines. This is especially important when we go to the small village of Kamyanka south of Kharkiv. Just a day before we arrived there with a humanitarian convoy, a boy stepped on a land mine in the village. Orest informs us of how we should act:

“Mines are much more dangerous, so we stick only to sealed roads. If somebody wants to pee, you pee just turning around. You don’t go to the bush because it’s a risk. There can be mines. So, don’t get too focused on the camera and you step on something.”

More than Common Sense

Drawing from the briefing, it’s clear that safety precautions aren’t just about common sense; they’re more advanced. Turning off location tracking on phones and sticking only to sealed roads are precautions one might not consider before heading to a conflict zone. The incident close to the hotel in Kharkiv, where a missile had hit close by, paints a stark picture of how real and immediate the dangers can be.

Being prepared to face such situations and having a necessary action plan significantly improves one’s safety.

The stringent security measures we experienced were eye-opening, especially the firm instruction to turn off location settings on our devices to avoid potential threats. Encountering the piercing reality of landmine dangers was quite sobering, especially when navigating through the small village south of Kharkiv the next day. The layers of safety protocols and the constant risk management add a different dimension to travel, one that carries a strong note of gravity and respect.

Ethic Visiting Country at War?

Additionally, we all considered the ethical ramifications and wanted to ensure that we were respectful of the situation, and local sentiments are a must.

Travelling to conflict areas may seem like a reckless idea to many, but it requires a deep understanding of the current situation and serious acknowledgement of the potential risks involved. This level of travel isn’t about getting adrenaline kicks from danger. It’s about witnessing the human condition in such circumstances first-hand, experiencing the resilience of people persisting through adversity, and extending support by visiting and sharing their stories. The ethics behind touring countries during conflict is largely about the balance between respect for those living in such circumstances and fuelling personal growth through understanding complex global situations.

From personal experience, the intensity of this balance was felt during the visit to Ukraine.

NomadMania, a community for extreme travellers, organizes the week-long visit to Ukraine. In their trip report on their website, they write:

“As the time came closer for a carefully planned NomadMania Ukraine Tour that was truly intrepid, the team was feeling anxious. To what extent were they responsible for those joining? And to what extent was NomadMania really doing the right thing by going to a warzone? Was it ethical or not? Courageous or just plain stupid?”

Negativity from the Travel Community

Not everyone understands why we chose to go to a country at war. And some people expressed their thoughts about what we were doing on social media.

- “I’m sorry, this is f*cking gross…”

- “Yikes. The idea of going to Ukraine right now, while they’re being attacked, is absurd and disrespectful.”

- ”F*ck that! You’re there because you want to brag about traveling to a war zone.”

- “That is so cringe and disgusting. OMG.”

- “That’s disgusting, and they should be ashamed.”

It doesn’t surprise me – and to some extent, I get it. I had my concerns before going there. Not just for my own safety but also, just … is it ethical? I spoke a lot to Orest, and as a Ukrainian, he knows better than anyone if this is disrespectful to his people or if they would see it as a sign of respect. I also had a long conversation with Harry, the founder of NomadMania. His partner is Ukrainian, so he would also know first-hand how the locals would perceive a visit like this.

NomadMania Response

Here’s what NomadMania wrote in an Instagram post after the tour:

“There is an assumption in the international travel community that visiting a country at war is unethical. What are you going to do there? Film destroyed buildings? Speak to impoverished locals? Put yourself at risk and make your family worried?

It could make sense! But why did every self-respecting European president visit Kyiv as soon as the Russian troops were pushed back in April 2022?

Correct! A personal visit (anywhere) is a basic act of support which is usually necessary for any further, more meaningful steps. It provides an in-depth feeling and understanding of the situation on the ground, not through a screen and other’s interpretation. Moreover, people in crisis areas often feel left out. Thus, everything starts with a handshake and a hug.

We at @nomadmania started our Educational #Ukraine Visit in Izyum, probably the most badly damaged midsized city, which used to be under occupation for half a year and was liberated in September last year.

No one greeted our group as warmly as the people of Izyum, who live 50 km from the front line.

Was it risky? Yes! Just a day before we arrived, a boy stepped on a land mine in the village of Kamyanka, where we came with the humanitarian convoy. A few weeks earlier, not far from Izyum, over fifty people got killed by a single ballistic rocket launch while having dinner in Hroza.

Fortunately, nothing bad happened if you could only see the eyes of local people who greeted us with open arms and provided snacks, which lasted all the way until Lviv.

Such visits give gope.”

Support and Solidarity

Delving deeper, travelling to conflict zones isn’t merely about the thrill of it. It’s also about extending support and solidarity to regions that are often forgotten or ignored by the majority of the world. Experiencing these places first-hand allows for a deeper understanding of the realities on the ground, breaking away from mere news stories and second-hand accounts.

While ensuring that one’s safety measures are well in place, by visiting these regions, travellers can contribute to their local economies and bring back stories that help raise awareness and understanding about these places and their people. This personal experience can then lead to more informed conversations and actions that can help areas in crisis. For instance, in this case, understanding that despite the ongoing conflict, most Ukrainian cities have low crime rates, Orest says.

” Everywhere in Ukraine is super safe. Like, there is zero street crime. When people think of the war, they think that there are some ambushes. People fight on each other on the streets. Here we have a classic World War II scenario with a frontline. And beyond the frontline, nothing is happening. So, you can do pictures, smile, no problem at all. Every city in Ukraine, in terms of the street crime and violence is much safer than every city in the United States. Like for sure.”

Life Goes On

Outside the hotel, where Orest is giving us the safety briefing, we can see the life in the streets of Lviv. Restaurants, shops, and bars are open; festivals and conferences and street performers are happening. But also, in Kyiv and even in Kharkiv, events are happening.”

“In our case, the biggest dangers are missiles. But one rocket missile costs over a million dollars. So, they are very selective where to hit them. But I have to warn you, and everybody has to accept that this is not a joke.”

Our visit is not about the feel of travel or the rush of danger; it’s about understanding the unseen narratives of war-stricken nations. It is a potent reminder that while we can leave a conflict zone, people who live there cannot. They hope, resist, and continue in misfortune, showcasing human perseverance. So, a conscious visit like ours isn’t about invading their space but about providing solidarity and empathizing with their situation, plus human connections and global understanding.

Such engagements bring sobering and humbling lessons, questioning our perspectives and assumptions and broadening our worldview. It is a journey across borders and into the depths of human tenacity and resilience.

Much More to Come

In the next episode, we get on a fifteen-hour train ride across the country. More than a thousand kilometres from Lviv to Kharkiv, close to the front line.

Here, we meet the locals as we visit a small village that has been completely destroyed. We go there with an NGO and help hand out humanitarian aid to the few locals who have decided to return.

In Izyum, south of Kharkiv, we have a conversation with some women sewing camouflage nets and go on a walking tour of Kharkiv – what used to be the second biggest city in Ukraine.

Make sure to listen to that one – and please share this episode on your social media platforms. The world needs to hear about what’s going on in Ukraine.

My name is Palle Bo, and I gotta keep moving.

See you next week.

I WOULD LIKE TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Please tell me where are you and what are you doing as you listen to this episode? You can either send me an email on listener@theradiovagabond.com, go to TheRadioVagabond.com/Contact or send me a voice message by clicking on the banner.

Either way, I would love to hear from you. It’s so nice to know who’s on the other end of this.

SPONSOR

A special thank you to my sponsor, Hotels25.com, who always provide me with the best, most affordable accommodation wherever I am in the world.

Hotels25 scans for prices on the biggest and best travel sites (like Booking.com, Hotels.com, Agoda and Expedia) in seconds. It finds deals from across the web and put them in one place. Then you just compare your options for the same hotel, apartment, hostel or home and choose where you book.

When you book with Hotels25, you get access to 5,000,000 hotel deals. And it’s “best price guaranteed.”

PRODUCED BY RADIOGURU

The Radio Vagabond is produced by RadioGuru. Reach out if you need help with your podcast.